Monday 30 March is World Bipolar Day (WBD), although few people know about it in the UK and Europe, not even my psychiatrist.

It is an initiative of the International Bipolar Foundation, San Diego, the International Society for Bipolar Disorders, Chicago, and the Asian Network of Bipolar Disorder, Hong Kong.

The date of March 30 was chosen as it is the birthday of the Dutch painter, Vincent van Gogh, who was retrospectively diagnosed to have had this disorder by various psychiatrists. The first World Bipolar Day was celebrated in 2014.

Van Gogh was born in 1853, but only lived to be 37. On July 27, 1890, he walked into a wheat field and shot himself in the chest with a pistol. He died a few days later.

In van Gogh’s time, there was no access to any medication to alleviate his condition. If there had, he might have left a much greater collection of masterpieces. A high proportion of bipolar sufferers commit suicide, as much as 15%, and many others attempt it.

Those with bipolar are often very creative individuals who contribute a lot to society. Examples include Stephen Fry, Mel Gibson and Frank Sinatra. The aim of WBD is to increase awareness of bipolar disorder and to eliminate social stigma, as well as informing the world about it.

Bipolar is a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels and the ability to carry out everyday tasks.

Symptoms of bipolar disorder are severe and different from the normal ups and downs that everyone experiences.

An estimated 1.3 million people in the UK suffer with bipolar, previously known as manic depression, according to the charity Bipolar UK. Diagnosis is not easy and can take up to 10 years or more. Most are diagnosed in their late teens or early twenties. There are two main forms, Bipolar I and Bipolar II, with the latter having less extreme bouts of mania.

About 5% of Bipolar I sufferers only experience manic episodes and do not get depressed. What causes bipolar is unclear although genetic and life circumstances play a role. Some women can suffer from it after childbirth.

The Australian researcher John Cade had the first paper published in 1948 showing that lithium carbonate is an effective mood stabiliser and anti-manic agent.

Danish researcher Mogens Schou subsequently confirmed the efficacy of lithium in further research and it was introduced into psychiatric practice. It became widely used from the late 1960s, although doses have reduced somewhat.

It is not effective for everyone and can also affect thyroid and kidney function.

Studies in Texas, Austria and Japan have found that high lithium levels in the water supply correlated with lower suicide rates in the populations.

Long-term exposure to lithium increases grey matter, which is generally better for the brain, and also possibly helps with dementia.

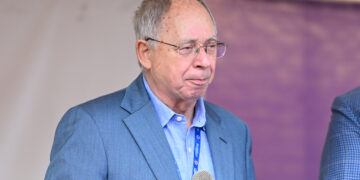

Professor Allan Young, Chair of Mood Disorders at King’s College London says there is no doubt that lithium prevents recurrence of manic episodes. It is less effective against acute depression.

He is working on better lithium formulations with less potential damage to kidneys. Professor Young commented that current treatments with lithium and other products show nowhere near the efficacy and selectivity of cancer treatments and this is something that needs to be rectified.

Current research efforts focus on biological causes, new targets for drug treatment, better treatments, better diagnosis, genetic components and strategies for living well with bipolar disorder.

Some 300 delegates attended a conference organised by Bipolar UK in London on November 17, last year, over half of whom were bipolar.

There was a panel session, which was also filmed by BBC TV’s Horizon for a future programme about the comedian, Tony Slattery, due to be broadcast this year.

The panel of four, including Slattery, debated whether they would prefer to remain bipolar or turn it off and eliminate the condition permanently. All four acknowledged that they owed their careers and creativity in part, at least, to being bipolar.

Bipolar UK took a poll of 85 bipolar attendees before the conference took place. Some 76% replied that they would turn off their bipolar if they could.

In a poll at the end of the panel session, some 65% of bipolar attendees indicated that they would prefer to eliminate their bipolar condition.

This suggests a substantial minority of sufferers sees their condition as providing something positive for their lives, despite the considerable drawbacks that come with it.